In 2024, cepezed celebrates its 50th anniversary. Among other things, we will celebrate this with a series of lectures. In this series, visual artist Ienke Kastelein shared her fascination for wunderkammers with us. In honour of the jubilee, cepezed will also set up a Wunderkammer as way of an alternative portrait of the office.

being present

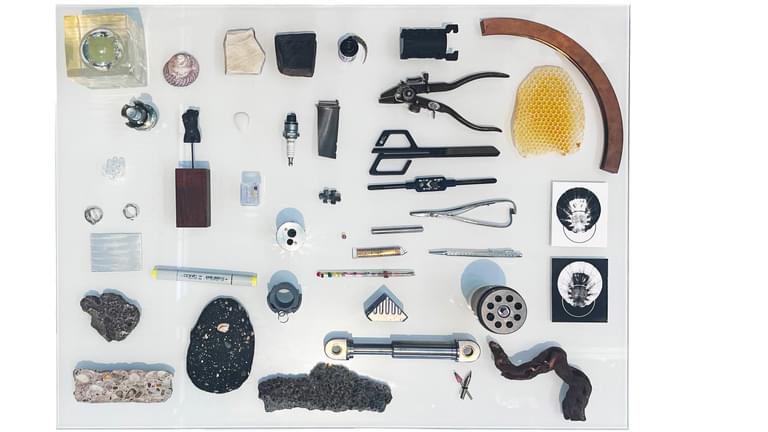

Three lego ducks, a spark plug, puzzle pieces held together by a string, a piece of honeycomb, a paving stone? Voilà the first objects of the cepezedwunderkammer. In the coming months, a unique collection of objects, contributed by the people of cepezed, will emerge for our 50th anniversary. Objects of personal value, which inspire colleagues and as a collection will show what drives the peoptle at cepezed.

To help us choose an object and to explain what a wunderkammer actually is, we invited Ienke Kastelein for a lunch lecture. As a visual artist and art historian, Ienke is interested in the dynamics between objects, between people, and between people and objects. She translates her fascination into installations and performances, as well as video and photography. ‘My whole body of work is a research and a reflection on being present and presence itself’, says Ienke.

kaleidoscopic

In a kaleidoscopic lecture, Ienke made it clear that the wunderkammer phenomenon can yield a seemingly endless series of associations. The lecture was titled 'In search of the miraculous: wandering in wunderkammers. Gleaning images, texts and quotations' for good reason: Ienke gleaned images, texts and quotations for us. Literally the German word 'wunderkammer' translates to a room where you can wonder, amaze and marvel. The Dutch translation ‘rariteitenkabinet’ and the English 'cabinet of curiosities' speak for themselves in this regard.

Ienke's narrative meandered past historical, philosophical, personal, social and artistic facets involved in collecting things. Not all information was ready-made; Ienke, for instance, presented us with questions about the meaning of a 'thing' in itself. Are things on an equal footing with people? Do they perhaps even have rights, and how do they relate to each other? Does a wunderkammer say something about our knowledge, or is it rather a portrait of the collector in question? And can the strictly personal value of a thing be significant to others?

thing of meaning

For Ienke, a fascinating example of a 'thing of meaning' is the apple. From a biblical perspective, in the apple lies the knowledge of good and evil, but also, thanks to Eve, the fall from paradise. Personally, Ienke associates apples with her grandmother: the tree in her grandmother's backyard, the picking, and how the apples were left to dry in the attic, their smell and their wrinkled skin. The seeds in the heart of an apple represent the enigma of life itself. In short, every apple involves a story, and that is true of almost all things.

When talking about 'things of meaning', art objects are an interesting example - they carry meaning by definition. Ienke demonstrates this through the work of dada artists and 'One and three chairs' by Joseph Kosuth. She reminds us that the meaning of an object has everything to do with the way we look at things, or in other words with our culture: 'We see things not as they are, but as we are'. Without a culturally determined filter, there would be a flood of signals coming in. So it protects us from chaos and meaninglessness, but in this way it might exclude certain meanings. Artists filter less, in a different way, or actually denounce culturally determined viewing.

wandering in wunderkammers with ienke kastelein

teylers museum

Maybe, precisely because of our 'filters', the appeal of a wunderkammer is its apparent chaos. The first cabinets of curiosities date from the early sixteenth century, with objects reflecting voyages of discovery undertaken from the Western world - from the objects, you could draw up 'discovery maps', so to speak. Originally, a wunderkammer contains an encyclopaedic collection. Over time, the collections became more personal, more and more reflecting the owner's wealth, or how well-travelled he was.

A great example of such an encyclopaedic collection is the Teylers Museum, which features the eighteenth-century wunderkammer of silk merchant Pieter Teyler. Ienke highlights a few examplary objects, including telephone cables from the nineteenth century, which crossed the Atlantic, and a foetus preserved in formaldehyde. In a jar with a label on it, that foetus has become a scientific object, or a 'thing'. While it was once animate and, still born, probably caused personal grief.

collecting drive

British psychologist Christian Jarrett studied our relationship with objects. 'Stuff everywhere', Ienke quotes Jarrett. 'Bags, books, clothes, cars, toys, jewellery, furniture, iPads. If we're relatively affluent, we'll consider a lot of it ours. More than mere tools, luxuries or junk, our possessions become extensions of the self. We use them to signal to ourselves, and others, who we want to be and where we want to belong. And long after we're gone, they become our legacy. Some might even say our essence lives on in what once we made or owned.'

This brings her to the example of Amsterdam's Rokin metro station and other collections consisting mostly of everyday objects. The walls of the metro station display the objects unearthed during its construction. This is a huge collection of 'stuff', ranging from a piggy bank and marbles to a mobile phone. People who live on the street carry bags full of stuff with them, that you could also call collections. For others, the urge to collect becomes irresistible and 'stuff takes over'.

We will try to prevent that at cepezed, which does not mean we already know the outcome. Colleagues submit objects for the wunderkammer that they cherish, that reflect their relationship with cepezed, that say something about a detail or about the meaning of architecture in general. They are bound to a small format, but otherwise free in their choice.

Ienke Kastelein is a Utrecht-based visual artist. Her work has been exhibited domestic and international and she has taught at various academies. In 2013, she won the Boellaard Prize, a bi-annual, Utrecht award for inspiring artistry.

→ Mail bd@cepezed.nl or call our business development team on +31 (0)15 2150000